Leading medical scientists and clinicians are calling on the World Health Organization (WHO) to revise its guidelines, advocating for the replacement of standard surgical face masks with higher-grade respirators in healthcare settings. The argument centers on the inadequacy of surgical masks in preventing the spread of airborne pathogens, including influenza and COVID-19, where protection against tiny particles is essential.

The Case for Respirators

The experts argue that current surgical masks offer insufficient filtration against airborne viruses. These masks were originally designed to prevent doctors and nurses from contaminating patients during procedures – not to protect them from infectious aerosols. Respirators, such as FFP2/3 (UK) or N95 (US) masks, provide a significantly higher level of protection, blocking approximately 80% to 98% of airborne particles compared to the roughly 40% filtration rate of surgical masks. This difference, as one expert puts it, is akin to falling from four inches versus four feet: a reduced risk, though not zero.

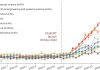

The push for respirators isn’t just about improved protection; it’s about preventing burnout and sickness among healthcare workers, who face higher infection risks. The pandemic saw an estimated 129 billion disposable face masks used monthly, and while many countries eventually shifted to recommending higher-grade masks as evidence mounted, the WHO guidelines haven’t kept pace.

Why This Matters Now

The debate over mask effectiveness is not new, but the pandemic exposed critical gaps in existing recommendations. While some governments adapted to recommend respirators, a standardized global approach remains absent. The WHO’s procurement infrastructure could significantly increase access to respirators, even in resource-limited countries, if it updated its guidance.

The issue extends beyond mere efficacy. The politicization of mask-wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic, as seen in the UK, highlights the cultural resistance to such measures. However, experts emphasize that this change would apply primarily to healthcare settings, where the risk of infection is highest.

The Science Behind the Shift

The call for respirators isn’t based on theoretical models but on laboratory tests showing their superior filtration capabilities. Critics argue that randomized controlled trials are needed to prove the effectiveness of physical barriers. However, proponents contend that such trials are flawed, as participants rarely adhere to 24/7 mask-wearing, creating exposure gaps.

Furthermore, they urge the WHO to explicitly acknowledge the airborne transmission of respiratory viruses, correcting past statements that may have downplayed this crucial route of infection.

The WHO has acknowledged the letter and says it is carefully reviewing its Infection Prevention and Control guidelines. The change could have a profound impact, but the question remains whether the organization will act decisively on this evidence-based recommendation.

This shift in guidance is not just a technical adjustment; it’s a recognition that better protection for healthcare workers and patients requires acknowledging the limitations of current practices and embracing more effective tools.